Unveiling Facts and Dispelling Fiction About Kibera.

Kibera, located in Nairobi, Kenya, is one of Africa’s largest informal settlements, capturing attention for both its challenges and its resilience. Let’s sift through the facts and fiction surrounding this unique community:

Fact: High Population Density: Kibera is densely populated, with estimates varying from several hundred thousand to over a million residents. This tight living situation leads to infrastructural strains and limited access to basic services.

Fiction: Lack of Community Spirit: Contrary to misconceptions, Kibera is a vibrant and close-knit community. Residents often support each other, collaborating on projects and initiatives that address shared challenges.

Fact: Informal Housing: Most of Kibera’s housing is informal, constructed from materials like corrugated iron sheets and mud. The lack of formal planning and infrastructure poses risks during natural disasters like floods.

Fiction: Hopelessness: While poverty is a reality, the people of Kibera exhibit remarkable resilience. Many are engaged in businesses, education, and community activities, striving to improve their lives and surroundings.

Fact: Limited Access to Services: Access to clean water, sanitation, healthcare, and education remains challenging for many Kibera residents. Informal settlements often struggle to receive the same services as formal urban areas.

Fiction: Lack of Creativity: Art, music, and cultural expression thrive in Kibera. The community showcases creativity through initiatives like youth groups, art collectives, and even an annual film festival.

Fact: Economic Struggles: Unemployment and underemployment are significant issues in Kibera. Many residents engage in informal work, from street vending to small-scale entrepreneurship.

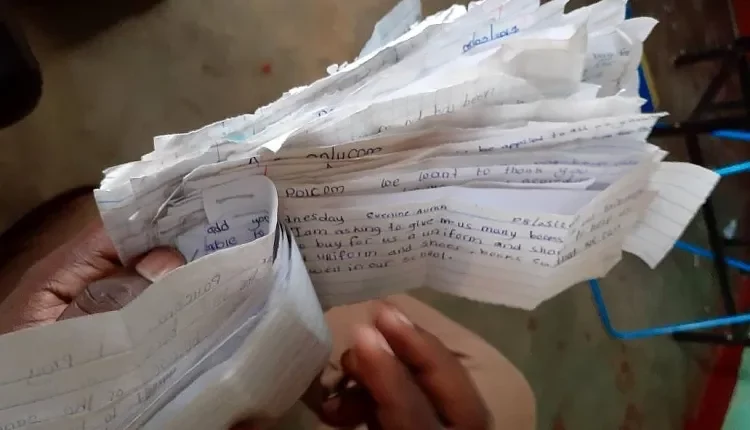

Fiction: Absence of Education: While educational opportunities can be limited, many organizations and individuals work to provide schooling and skill development programs for Kibera’s youth.

Fact: Resilient Spirit: Despite challenges, Kibera’s residents display remarkable strength and resourcefulness. Grassroots organizations and initiatives are actively working to improve living conditions and empower the community.

Fiction: Uniformity: Kibera is not a monolithic entity. It has diverse cultures, religions, ethnic groups, languages, and backgrounds, reflecting the rich mosaic of Kenya’s urban landscape.